The spine is a complex structure, comprised of nerves, connective tissue, bones, discs, muscles and other essential integrative components. Specifically, the cervical spine is a vulnerable area that is commonly injured due to fall, trauma, motor vehicle accident, stress, as well as poor ergonomic setups, which all lead to pain. In this article, we will review the anatomy of the neck, common injuries to the cervical spine, functional assessments and training strategies to work with clients with previous injuries.

Basic anatomy

When we look at the neck, there are seven bones(vertebrae) that are part of the supportive column of the spine. Within the cervical region, there are several key anatomical structures that include; spinous process, transverse process, and facets, which are an articular surface within the bone that allows gliding of bones to occur. In addition, there is a disc between each two bones, that provides cushion and support, which is surrounded by an annulus, which is made up thin, type I collagen fibers, which protects the disc.

There are over 700 muscles in the human body. Each with a specific function and task. The primary muscles that support the neck are the upper trapezius, scalenes, levator scapula as seen in figure 5. Per the research and Vladamir Janda, the upper trapezius, scalenes and levator scapula are considered postural muscles, that tighten over time. Whereas, the rhomboids, middle and low trapezius, weaken over time, and are called phasic muscles.

Lastly, each bone has two peripheral nerves that functions to sense(interpret) information as well as produce movement(motor).

Figure 3. The spine

Figure 4. Components of the spine

Figure 5. Muscles of the neck

Common injuries and causes of cervical spine

There are several types of injuries the cervical spine can sustain. The most common are cervical whiplash, osteoarthritis, disc injury including pinched nerve(radiculopathy.

a. Cervical whiplash

Mechanism of injury/pathophysiology: The term “whiplash” commonly refers to symptoms and signs associated with a mechanical event such as a sudden acceleration and deceleration of the neck. Usually seen in a motor vehicle accident(Bono et al 2000).

Sign and symptoms: In the acute phase, there is complaints of localized sharp pain, and pain that either travels up or down the neck. The individual’s muscles are guarding, swelling of neck musculature with accompanying spasming. This makes any type of movement painful and

difficult. Patients may also experience dizziness, immediate or shortly thereafter the accident.

b. Cervical osteoarthritis(degenerative disc disease)

Mechanism of injury/pathophysiology: Is termed the wear and tear arthritis because it is thought that the articular cartilage breaks down because of an imbalance between mechanical stress and the ability of the joint to handle the given loads. This biomechanically creates decreased space between the vertebra and possible bone spur development as seen in figure below. Factors that can influence the development of O.A. include; excessive weight, repeated repetitive stressors, and muscle imbalances.

Sign and symptoms: Pain in the a.m. described as “achy” and stiff that decreases as the day progresses, and worsens or become more fatigued by the end of the day.

Figure 6. Osteoarthritic/degenerative spine

c. Cervical Radiculopathy(due to a pinched nerve)

Mechanism of injury/pathophysiology: This is where the cervical nerve root is being compressed, resulting in inflammation, creating local to peripheral pain(arm). Irritation to the nerve root can result from mechanical derangement in or about the intervertebral foramen. The most common causes are a muscle pinching on a nerve, joint(two bones) compressing the nerve or a disc pushing on the involved nerve.

Sign and symptoms: Individual will describe pain as sharp, achy, burning located in the neck, shoulder, arm or chest, depending upon the nerve root involved. Individual will also complain of vague pins and needles that come and go in the whole hand and possible weakness (Greathouse 2010).

Medical mgt: Patients may be advised by their physicians to take NSAIDs, have x-rays taken that reveal no abnormalities, advised to rest and follow up with a physical therapist. Per the research, manual therapy combined with mechanical traction has superior results(Young 2009).

e. Cervical disc injury

Mechanism of injury/pathophysiology: A single incident, or motion that involves a combined movement of cervical flexion, rotation with side bending repeated over and over may be the direct cause for a cervical disc injury(Starkey, C., & Johnson, G., 2006). The lumbar is more at risk for sustaining a injury to the annulus and disc due to size and biomechanical structure, than the cervical region.

Types of disc injuries:

1. In Protrusion or bulge, there is change in the shape of the annulus that it causes to bulge beyond its normal perimeter.

2. In Prolapse disc(herniation), the ligamentous fibers give way, allowing the nucleus to bulge into the neural canal. The disc is still contained by the outer layers of the annulus and supporting ligamentous structures.

3. Extrusion is where the disc protrudes through the annulus but is contained by the posterior longitudinal ligament(PLL).

4. Sequestration is where the nuclear material/free floating piece of the nucleus has partially separated from the remaining nucleus, allowing it to be free in the neural canal and moves into the epidural space.

Sign and symptoms: Most cervical disc herniations occur posterolaterally, which explains the neck and unilateral arm symptoms that most patients complain of. They will also complain of constant sharp pain, numbness, and possible weakness(Starkey & Jones 2006).

Medical mgt: Patients receive a thorough examination, x rays may reveal degenerative changes such as disc space narrowing or osteophytes present. A MRI is the most useful test in evaluating the integrity of the soft tissue and structures of the cervical spine.

Common Assessments

For safety and based on the clients past medical history, length of time from injury and general health, I would recommend the following assessments. First, examination of their posture from all planes. This provides invaluable information about muscle guarding, muscle imbalances and possible compensatory patterns. Second, I would look at range of motion of their upper and lower body. Specifically, looking at the quality and manner they move. Is it smooth, juttering, shaky, guarding? Another assessment I would look at is functional movements such as a squat or a lunge, which tells you about the entire kinematic chain, from the foot to the neck.

Figure 7. Side view of faulty posture

Training strategies and programming for neck injuries

With any injury, the most important thing to remember is the type of injury, healing time and prior level of function of the client.

a. Whiplash injuries

Whiplash injuries can take a long to heal ranging form 3 months up to one year in duration.(Gargan 1994). There is considerable research that states that those who suffer a whiplash injury, often experience ongoing pain and disability for an extended period after their car accident(Kamper et al 2008).

Recommendations for training: Based on evidenced based research, physics and my personal experience having suffered a motor vehicle accident in 2009, I would avoid having a client perform any overhead motion, such as shoulder press, kettle bell exercises, squats with barbells on the upper trapezius and performing any unsupported exercise as seen in the figure below.

Figure 8. Unsupported exercise

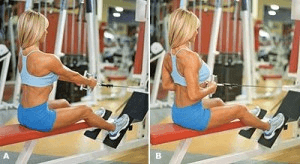

Clients would benefit from a personalized program that consists of program design that meets their fitness goals and medical history. Specifically, exercises that target the posterior musculature, focusing on rhomboids, mid and low trapezius, low back extensors, and posterior deltoid. These will unload the neck biomechanically and improve posture and stability. Core strengthening should begin statically and progressed dynamically per the client’s ability to maintain form. Functional lower extremity strengthening should also be included and again personalized.

Figure 9. Seated mid row exercise

b. Cervical degenerative disc disease(DDD)

Recommendations for training: I would teach them self-stretching of the upper trapezius and pectorals, which are commonly tight. Strengthening should focus on weaker, phasic muscles(rhomboids, low trapezius), also strengthening the Latissimus dorsi, medial deltoids and periphery. Core strengthening should always play an integral role in your program design. Lastly, cardiovascular conditioning should be personalized and tailored to the goals of the client. Based on evidenced based research and physics, avoid having a client perform any overhead motion, such as shoulder press, kettle bell exercises, squats with barbells on the upper trapezius and performing any unsupported exercise. These all place unnecessary stress on the cervical spine.

c. Cervical Radiculopathy due to pinched nerve

Recommendations for training:

Most clients will have completed physical therapy before meeting them and it would be an excellent segway from rehabilitation to the gym, to contact the clients physical therapist with their permission. This educates you on the severity of their previous injury, opens communication and can be an excellent marketing opportunity. Training should consist of targeting the weaker rhomboids, mid and low trapezius and back extensors. Core strengthening exercises should always be included, but do not directly load the cervical spine. Technique, quality of exercise and personalization, should be the priority with the program design of your clients program.

d. Cervical Radiculopathy due to disc injury

Recommendations for training: Most clients will have completed physical therapy before meeting them and it would be an excellent segway from rehabilitation to the gym, to contact the clients physical therapist with their permission. This educates you on the severity of their previous injury, opens communication and can be an excellent marketing opportunity. Core strengthening exercises should always be included, but do not directly load the cervical spine. Technique, quality of exercise and personalization, should be the priority with the program design of your client’s program design of your clients program.

Summary

The neck is a complex unit that is comprised of a multitude of ligaments, tendons, connective tissue, muscles that synergistically initiate and correct movement, and stabilize when an unstable environment. Understanding the anatomy, biomechanics and weak links of the neck, common injuries and evidenced based training strategies, should provide you with the insight to better understand and work with clients with these kind of injuries more confidently.

Chris is the CEO of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems(PTCS). A continuing education company, that provides educational material in the forms of home study courses, live seminars, DVDs, webinars, articles and min books teaching in-depth, the foundation science, functional assessments and practical application behind Human Movement, that is evidenced based. Chris is both a dynamic physical therapist with 14 years experience, and a personal trainer with 17 years experience, with advanced training, has created over 10 courses, is an experienced international fitness presenter, writes for various websites and international publications, consults and teaches seminars on human movement.

REFERENCES

Bono, G, 2000, ‘Whiplash injuries: Clinical picture and diagnostic work-up,’ Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, pp. 22-27.

Delee, P, 2010, ‘Orthopedic Sports Medicine,’ Saunders Elsevier, pp. 658-661.

Gargan, M.F., & Bannister, G.C., 194, ‘The Rate of Recovery Following Whiplash Injury,’ European Spine Journal, vol. 3, issue 3, pp. 162-164.

Gifford, L, 2001, ‘Acute low cervical nerve root conditions: symptom presentations and pathobiological reasoning,’ Manual Therapy, vol. 6, issue 2, pp. 106-115.

Greathouse, D, ‘Radiculopathy of The Eighth Cervical Nerve,’ JOSPT, vol. 40., no.12, pp. 811-817.

Kamper, et al., 2008, ‘Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: A systematic review and meta-analysis,’ Pain, vol. 138, pp. 617-629.

Starkey, C., & Johnson, G., 2006, Athletic Training & Sports Medicine. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Boston. pp. 530-540.

Young, I, et al., 2009, ‘Manual Therapy, Exercise and Traction for Patients with Cervical Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial,’ Physical Therapy, vol. 89, no. 7, pp. 632-640.

- 9shares

- 9Facebook

- 0Twitter

- 0Pinterest

- 0LinkedIn

Chris Gellert

Latest posts by Chris Gellert

- Training the Impingement Client - August 16, 2016

- Working with the older client Part 1 - May 25, 2016

- The Cervical Spine – Understanding The Science Behind Both Movement And Dysfunction - December 10, 2014